War Memorial Hall c1929

Robert Alexander (called ‘Alec’ and ‘Rick’) LITTLE

Alec Little was born on 19 July 1895 in Hawthorn, Victoria. His parents were James and Susie (née Solomon) Little. He attended Scotch from 1907 to 1912. He won a school swimming medal, which was among his personal possessions at his death.

Alec was a commercial traveller before he enlisted on 14 January 1916 at Eastchurch, England. He served in the 8 Squadron RNAS, 3 Squadron RNAS and 203 Squadron RAF with the final rank of Captain.

Alec died on 27 May 1918 at Norviz, France. He was 22 years of age.

Service record

Alec Little was destined to be the most eminent and famous Old Scotch Collegian killed in the First World War. He was Australia’s most successful ever fighter ace. Yet when he tried to join the Point Cook Military Flying School in 1915 he, like hundreds of others, was unable to obtain one of the four places available. On 27 July 1915 he sailed from Australia for England, hoping to become an airman there. Several sources say he did this on his own initiative and at his own expense, though The Scotch Collegian’s assertion that his father paid for him to go seems more plausible. Alec or his father also paid for the training that enabled him to qualify as a pilot on 27 October 1915 at Hendon. In January 1916 he became a probationary Flight Sub-Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Air Service, based at Eastchurch, England.

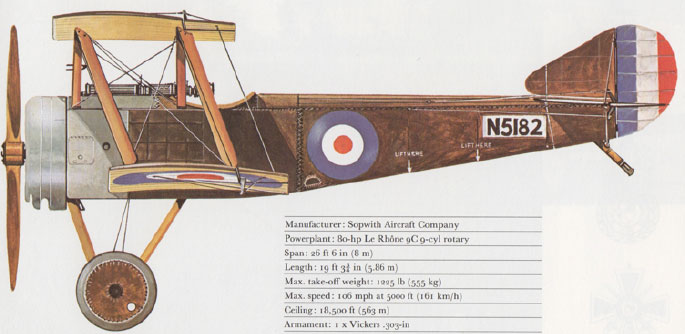

Fortunately his early service, at Dover, was relatively safe, for he struggled with stomach and eye problems in the air. This was probably due to castor oil coming back on him from the engine: the problem disappeared when he transferred to other aircraft types. At Dover he married Vera Field on 16 September 1916. By then he had been posted to No. 1 Wing at Dunkirk, in France, where since June he had been undertaking reconnaissance and attacks against the German submarine base at Zeebrugge in Belgium. In October he was transferred to the newly formed No. 8 Squadron, known as ‘Naval 8’. Between November 1916 and January 1917 he flew a Sopwith Pup, N5182, ‘Lady Maud’, which is now on public display at the RAF Museum at Hendon (see below). The pilots loved Sopwith Pups.

On 23 November 1916 he used his Pup to achieve his first aerial victory, over a German two-seater reconnaissance aircraft. Both its crewmen were killed. An extract from a letter he wrote to his father about his first combats is reproduced below. By February 1917 he had added another three victories and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for 'conspicuous bravery in successfully attacking and bringing down hostile machines'. His successes multiplied after April 1917, when the squadron converted to Sopwith Triplanes. Little had by 10 July taken his total to 28. On four occasions he shot down two aircraft in a single day. He called the Triplane with which he had most success "Blymp", a nickname he also applied to his son Robert.

New aircraft, Sopwith Camels, arrived at the unit in July, and that month Little used them to add 10 more of his 14 kills for that month. At about this time a letter from Alec was quoted in The Scotch Collegian. He wrote disparagingly of the tendency of newspapers to write of the ‘Huns’ having mastery of the air. Instead, he asserted, the Germans usually remained well behind their front line, near their aerodrome. Occasionally they came out in numbers. ‘Once I met 11 and I was alone’, he said of a celebrated occasion. ‘They tried to cross our lines, so I attacked the last man and shot him down’. Fire from the others damaged his oil tank, but Alec ‘turned and faced the 10 of them and they went for their lives. If there had been about 20 they might have fought me. I then glided back home.’

He told of another occasion when he surprised a German reconnaissance plane. ‘The Germans are afraid of the type I fly’, Alec crowed, ‘as it [is] about three times as fast as their fastest scout [fighter plane]. I have red streamers (flags) on each side of my machine, and he had heard of me before our meeting.’ This emerged after he forced the enemy aircraft to land. He had to crash land his own plane, but managed to capture the German aircrew, both of whom were sporting Iron Crosses.

In an example of chivalry without equivalent in the army, he took his two prisoners to dinner, where they were impressed by the available fare: meat, potatoes and especially sugar. Alec proudly reported that they had told him that Lieutenant Leefe Robinson was still alive. Robinson had won a VC and immense popularity for being the first to shoot down an enemy zeppelin bomber over Britain. He had been captured and now Little knew he was alive – though not for long. In August 1917 Alec returned to England for a rest. His skill and courage in achieving his 38 kills had been rewarded in various ways: promotion to Flight Lieutenant in April; a bar to his DSC in June (that is, a second award of the DSC); the French Croix de Guerre on 11 July, one of the first three awarded to British Empire pilots; the Distinguished Service Order ‘for exceptional skill and daring’ in August then in September a bar to that award ‘for remarkable courage and boldness’.

He was also Mentioned in Despatches that year. As the wording of his awards suggests, his aggressive approach in action, based on an apparent lack of fear, was vital to his success. That aggression allowed him to shoot at enemies from close range: he twice got so close to enemy aircraft that they accidentally touched. Nevertheless, he was an exceptional marksman who spent much of his time on the ground practising shooting at moving targets with rifles and pistols. He was blessed with superb eyesight, though as his frequent crashes attest, he was not a great flyer. Indeed his awkwardness at the controls nearly prevented his initial acceptance into the RNAS. He had a sensitive side, for example enjoying collecting wild flowers.

The Naval Air Service’s top ace, Raymond Collishaw, described Little as 'an outstanding character, bold, aggressive and courageous, yet he was gentle and kindly. A resolute and brave man.’ Alec’s squadron gave him the nickname ‘Rikki’, from the mongoose who kills Cobras in Rudyard Kipling’s story ‘Rikki-Tikki-Tavi’. Alec was said to be gregarious and ‘a great talker’ on the ground, but inclined to be a loner rather than a leader in the air.Nevertheless by January 1918 he was a flight commander. Rather than take a proffered desk job in March 1918 he voluntarily returned to France and joined No. 3 Squadron RNAS (‘Naval 3’), flying a Sopwith Camel. When the Royal Naval Air Service combined with the Royal Flying Corps on 1 April, No. 3 became No. 203 Squadron and Alec became Captain Little. He gained a further nine victories with this status, and survived being shot down on 21 April 1918, the day the Red Baron was killed.

However, his own death came barely a month later. He was flying alone to intercept German Gotha bombers on the night of 27 May when, as he closed on one of them over Norviz, his aircraft was caught in searchlights. An enemy bullet, fired from the Gotha or the ground, pierced both thighs and struck him in the groin. He crashed in a field. By the time a passing gendarme found him the following morning, he had bled to death. Alec Little was just 22 years old. His official tally of victories was 47: the highest of any Australian, eighth among all British Commonwealth aces and fourteenth of all World War I aces. His wife had these words inscribed on his headstone: ‘”Croix de Guerre with Star”/His ever loving wife/and little son Blymp. Also his loving father’. Little’s obituary in The Scotch Collegian says: ‘Shortly before his death, Capt. Little expressed the wish that, in the event of his death, his infant son should be educated at Scotch College.' His widow Vera did partly follow Alec’s wishes in taking his infant son to grow up in Australia, where he was educated at Wesley College. Alec’s continuing attachment to Scotch during the war is apparent in the fact that, according to Vera, on one occasion he flew with wingtip streamers in the school colours of cardinal, gold and blue. The quotation above concerning streamers on his wings suggests it may have been more than once.

His attachment to Scotch also emerged in an astonishing way in August 2013. A year earlier, a collector searching a rubbish tip in the small town of Texas, Queensland found a leather bag of items once belonging to Alec Little. A year later he took a closer look at what he had thought was a motorcycle helmet and discovered that it was war memorabilia. Inscribed on the helmet’s lining was not only ‘R.A. Little’ and his home address in Windsor, Melbourne, but also ‘Deo patria litteria’: a slightly inaccurate version of the school motto, ‘Deo, Patriae, Litteris’.

Alec Little is buried in the Wavans British Cemetery, France.

Photographs and Documents:

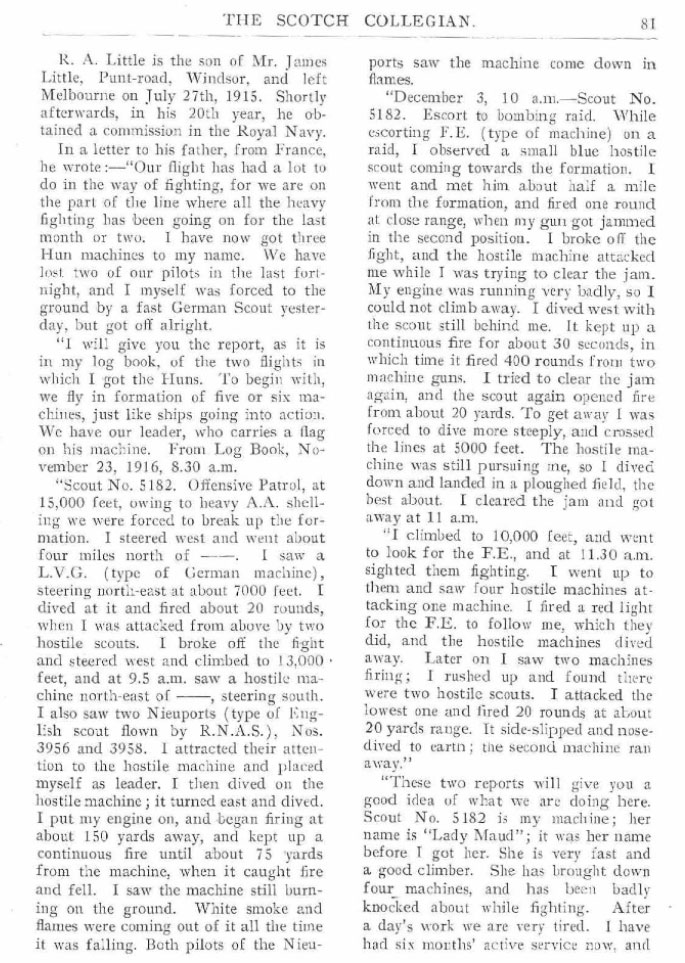

Extract from a letter from Alec Little to his father concerning his first aerial combats, reproduced in the 1917 Scotch Collegian. He quotes from his ‘log book’ or flying log. He refers to enemy ‘scouts’, a term used by the British for single-seat aircraft that would later be termed ‘fighters’. The last words of the letter, not reproduced here, are: ‘have not been caught. I hope to get through safely.’ Such hopes were tested on every sortie.

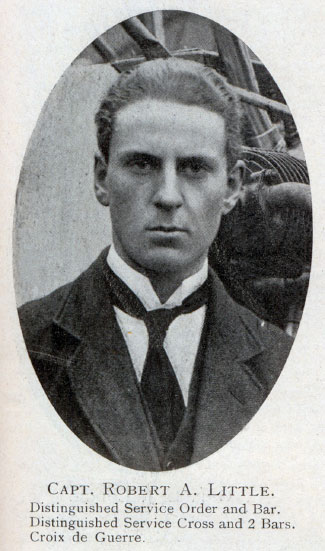

Portrait of Captain Alec Little

Portrait of Captain Alec Little

Portrait of Captain Alec Little

Captain Alec Little with his wife Vera. She said that his photographs did not show Alec’s sense of humour, but there is a trace of a smile here.

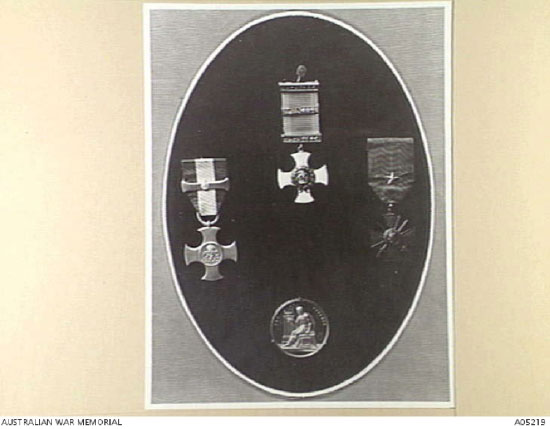

This photograph from the Australian War Memorial shows a collection of coveted military decorations belonging to Alec Little: Distinguished Service Order and bar; Distinguished Service Cross and Bar; French Croix de Guerre and Star. Alongside them (at bottom) is his Scotch College Swimming Medal!

Alec Little’s Sopwith Pup, at the RAF Museum, Hendon. Source:

Alec Little’s Sopwith Pup N5182. Source: Christopher Campbell, Aces and Aircraft of World War I

Alec Little’s headstone

Alec Little’s helmet, which was inscribed with his name, address and the school motto.

Sources:

- Australian War Memorial – Roll of Honour

- Campbell, Christopher, Aces and Aircraft of World War I, Treasure Press, London, 1981

- ‘Dogfighter from Down Under – Robert Little, Australia’s Top Great War Ace’, warnepieces.blogspot.com.au

- Little, J.C., 'Little, Robert Alexander (1895–1918)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/little-robert-alexander-7207/text12471.

- Mishura Scotch Database

- ‘Robert A. Little’, Wikipedia

- Rosel, Mike, Unknown Warrior: The Search for Australia's Greatest Ace. Australian Scholarly Publications, North Melbourne, 2012.

- Scotch Collegian 1917 and 1918