Roy William MCINDOE

Roy McIndoe was born on 18 November 1895 in Newport, Victoria. His parents were William Donald and Mary Marshall (née Campbell) McIndoe. He attended Scotch from 1910 to 1913. Roy won a Victorian government scholarship to attend Scotch. He was a Prefect in 1913.

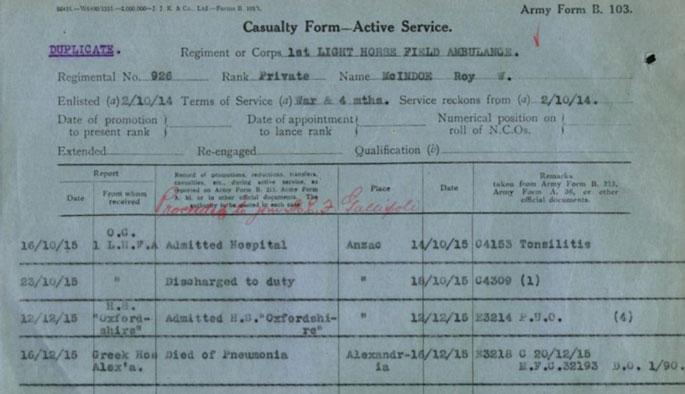

Roy was a medical student at the University of Melbourne when he enlisted on 2 October 1914 at Melbourne. He served in the 1st Light Horse Field Ambulance with the rank of Lance Corporal (the AWM Honour Roll has him as Corporal: he seems to have had acting rank as a Corporal). His Regimental Number was 926.

Roy died on 16 December 1915 at the Greek Hospital in Alexandria, Egypt. He was 20 years of age.

Service record

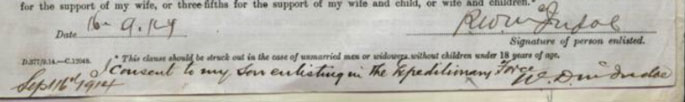

As Roy McIndoe was only 18 on enlistment, he required his father’s assent to his enlisting (See image below). Before the war he had been a Lieutenant in the 64th Battalion of the Citizen Military Forces. On enlistment this medical student was allotted to reinforcements for the 1st Light Horse Field Ambulance and joined that unit on 12 February 1915.

Extracts from his letters were published in the 1915 The Scotch Collegian. He said of his unit's arrival in HMAT Berrima at the Suez Canal in Egypt: ‘We entered the canal last and to stop at night at the first basin with half the fleet. The New Zealanders were entrenched along the banks waiting for the Turks, who were only two miles away in one part.’ While in Egypt, before the Gallipoli landings, he wrote of training incidents that recall the film Gallipoli. ‘We had a field day a few weeks ago’, he wrote, ‘when all arms were engaged firing ball [i.e. live] ammunition. We attacked a hill with dummy trenches, and head and shoulder targets. The infantry advanced, supported by light horse on the flanks, and with artillery firing shrapnel over their heads, and machine guns popping everywhere. It is a wonder nobody got hit. You may be sure that we [i.e. ambulancemen] didn’t get into the firing line that day, as we usually do.’ He told also how ‘every now and then some out of work officer appears, or, maybe a titled humbug, and wishes to see “the daring Australians.” The result is that the “daring Australians” are marched out to stand for hours on the burning desert while Sir Flippotty Flopdial canters across in front exclaiming, “Bai Jove, what jolly fine fellahs, what?” and the like.’

He wrote on about 30 May of being in a hospital ship off Gallipoli. Unfortunately the exact circumstances of what he was doing are unclear, but his note on what was going on ashore is interesting: ‘The Australians are wonderful soldiers and marvellous patients. The hill and fort at Gaba Tepe [a promontory south of Anzac Cove that the Australians never took, but here probably meant to denote the hills above Anzac] look impregnable, but they took it against overwhelming odds, and are now holding the trenches against thousands of reinforcements. Our boys accept wounds quite calmly, and bear pains with the patience of Job. One chap from South Melbourne had his arm amputated. The next day he was carried down on a stretcher to have it dressed, and came back whistling “On the Mississippi”.

A couple of days later he was walking about the deck in pyjamas as if nothing was the matter. Of the whole 800 cases that we treated only 15 died, and the rest were sent ashore in such good condition and so well dressed surgically that we have been specially commended. We have had a well earned rest for a couple of days, most of which I have spent yachting on the Mediterranean.’ He later wrote of travelling to the island Lemnos, probably in August, at the time of the costly offensives at Gallipoli. ‘We were no sooner at Lemnos than the work began. We got a constant stream of wounded on board. It was an enormous number to attend to, considering that there were only 17 men and 3 officers, and this small number had to work two shifts.’

His letter mentions Captain Fiaschi and the nurses on Lemnos, who will be familiar to viewers or readers of 'Anzac Girls'. Fiaschi selected McIndoe as one of three men to assist at the operating theatre. Roy was honoured to be selected, but it was demanding work: ‘We got the first batch of wounded at 5.30 one morning, and the three of us at the operating theatre did not turn in again till 5 a.m. the next morning, going solidly the whole time, with half-an-hour for meals. Then we started again at 9 a.m., and finished just after midnight. These hours continued until we got out to sea [possibly on the Galeka], when all lights have to be out at 10 p.m…[we] arrived at Malta yesterday with only 8 deaths out of 700 patients…We were sorry that we had so few Australians on board. They are the most cheerful beggars to look after, and easily the best patients.’

By October Roy was on the Gallipoli Peninsula. He was hospitalised for four days that month with tonsillitis before returning to duty. Then on 12 December he was admitted to the Hospital Ship Oxfordshire with P.U.O. (pyrexia of unknown origin, meaning a high temperature that could not be explained). Four days later he died at the Greek Hospital Alexandria. The diagnosis was pneumonia (medical record copied below).

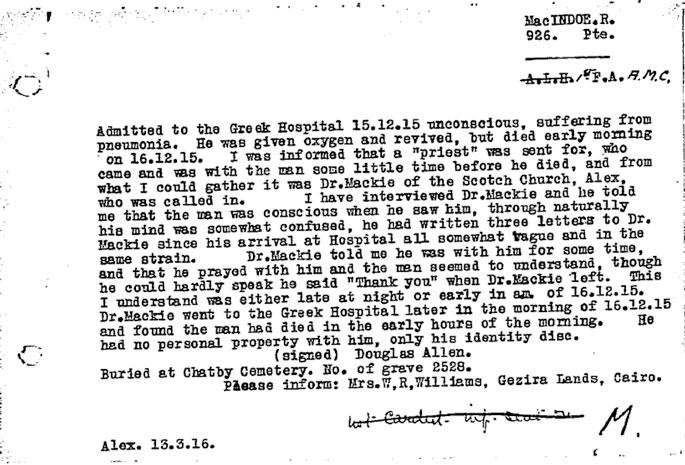

As a result of an inquiry from his family about the circumstances of his death, a letter about his last days appears in the Red Cross Wounded and Missing file (reproduced below). It makes for sad reading, as he was barely conscious in that period. In the 1916 The Scotch Collegian, an unnamed close friend said of Roy: ‘He came through the Gallipoli campaign without a scratch, and then, in December, developed pneumonia, and died in a few days. His memory will long remain with us – a lasting tribute to him. He played most games, but it is not as an athlete that we think of him; he shone in any sphere of intellectual pursuits; but our memory is not of a scholar – it is of something higher – a strong man. He was quite alone in his vigorous and graceful personality – a moving force in everything with which he was connected.’

Roy McIndoe is buried in the Chatby Military and War Memorial Cemetery, Alexandria, Egypt.

Photographs and Documents:

Consent for enlistment

From Roy’s Service Record - Casuality form

From Roy’s Service Record

Sources:

- Australian War Memorial – Roll of Honour and Red Cross Wounded and Missing file

- National Archives of Australia – B2455, MCINDOE RW

- Scotch Collegian 1915 and 1916

- The AIF Project - https://www.aif.adfa.edu.au/showPerson?pid=199171